Caretakers of death

Eight billion people on this planet share one thing in common – their own eventual death. It’ll happen to everyone, yet nobody wants to hear about it. Many never see death close up and try their best to forget about it.

But for some people, it’s simply their job.

In this special report, Nick Gascoyne gains an insight into three different occupations working with the deceased.

A trauma crime scene cleaner, a mortuary assistant and a forensic pathologist work for the dead and for the living. They will clean up after death, so loved ones won’t be reminded of it. They disguise death by embalming, so relatives don’t have to see it. And they perform autopsies to provide answers surrounding someone’s death so those left behind can grieve.

It is their crucial work that has allowed the public to comfortably distance themselves from where we all eventually end up. These are their stories.

The mortuary assistant

Hayleigh always apologises to her clients for her awful taste in music. She plays while she does their hair and make-up. But they never care, as they aren’t alive to hear it.

“Even though they are deceased, I was always taught to treat them like a person. I’ll talk to them about what's going on in the world and who's coming in to see them. I normally apologise if the water's a little cold or if it's the wrong brand of makeup they don't like,” says Hayleigh.

She calls herself a mortuary assistant, but the truth is she has many titles. To her clients, she is a hairdresser or a barber, she’s a make-up artist and a sculptor, and to some, she’s just an embalmer.

“I don’t think people know how much work goes into it behind the scenes. It isn't just a case of your loved one's already prepped and it takes half an hour beforehand. It can take hours, especially if you have a trauma patient who needs facial reconstruction using building wax,” says Hayleigh.

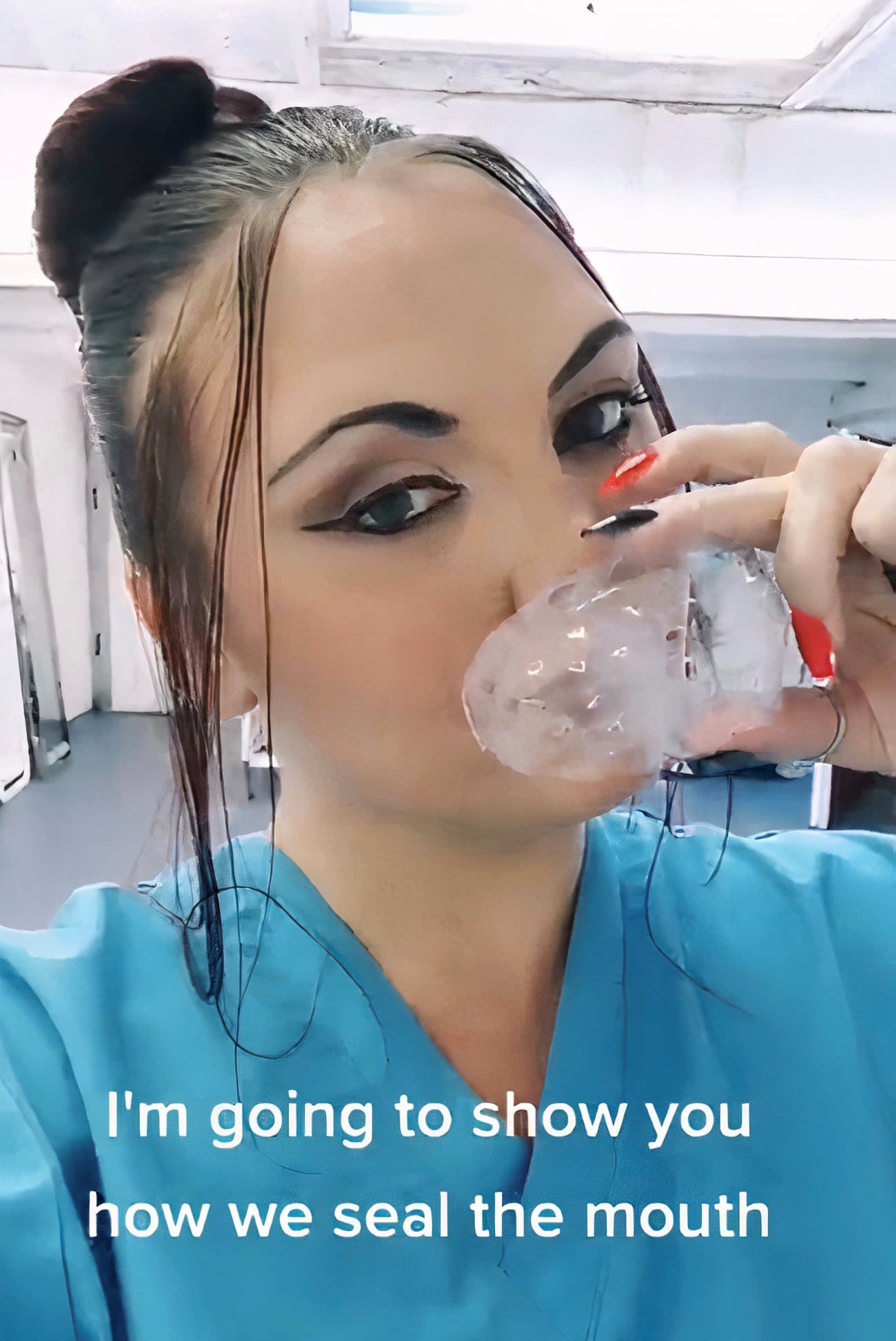

In an attempt to make her clients appear like they did when they were alive, many invasive procedures are taken, and they don’t always work. The eyelids would be closed for the last time using eye guards and the mouth would be sewn shut into its natural position, but no matter how hard Hayleigh tries, sometimes the embalming process of preserving the body won’t work.

“It's one of the biggest myths out there that embalming is going to make you look 10 times better. It's not. You can embalm somebody and then they can sweat it out quite quickly. Then you've got beads of sweat all over them, and we've got to explain to the family it’s made no difference and they have to pay for that,” she says.

“There can be times when you just need to take a breath and go sit in your car and cry.

This can be difficult to come to terms with and some days are more difficult than others. Over time it's possible to become desensitised to the sound and sight of death, but Hayleigh never forgets that with every dead person is a grieving family.

“There can be times when you just need to take a breath and go sit in your car and cry. It hits you that this is somebody's family member. This is real. This isn't TV.

"The hardest part is without a doubt little babies. I have lost three babies, so on a personal level that is hard. Suicides are also really hard because the families weren't expecting it, and you can just see the devastation on their faces,” says Hayleigh.

Preparing the deceased and making them presentable for family viewing is an intimate and close process. It requires you to get to know who the person was when they are alive. It’s an emotionally taxing job, but an incredibly important one.

“The rewarding part is giving the opportunity to families to say goodbye. Sometimes being able to say goodbye just brings so much comfort and closure to people, and not all the times in death that can happen.”

The forensic pathologist

Much like death itself, a post-mortem is not pretty, and every dead body has a different story to tell, says Patrick Hansma.

“There's an interesting phenomenon with overdose deaths, commonly called the heroin posture, sometimes called the fentanyl fold," he says. "It is a phenomenon where the deceased is essentially just folded over, face down on the floor, frequently on their knees or cross-legged, with their stomach against their thighs.

"I don't know why that is. It's not 100% specific, but for whatever reason. It seems to correspond most closely and frequently with opioid overdoses.”

Patrick is a forensic pathologist in Kalamazoo, Michigan who has performed hundreds of autopsies from children to decaying murdered bodies, to determine their causes of death.

A deceased body can leave clues and secrets that forensic pathologists can decipher to explain as to why somebody has died. Most of these clues are found below the skin, requiring Patrick to perform procedures that can in some cases result in the complete dissection of the body.

“There are basically four different categories of autopsy methods. One autopsy method is when you don't actually take anything out of the body, just dissect it all while it's still inside.

"The opposite extreme is when you take all the organs out all still connected to each other, then dissect them apart outside the body,” says Patrick.

“One of the more unfortunate things you have to put up with in forensic pathology is something called cheese skippers. They are a type of maggot that jump and for such a little critter they can fling themselves several feet in the air. It's not pleasant.

On a good day, this common procedure performed by Patrick is graphic, but it is made significantly more difficult and gruesome when working on a decomposing body.

“One of the more unfortunate things you have to put up with in forensic pathology is something called cheese skippers,” says Patrick. “They are a type of maggot that jump and for such a little critter they can fling themselves several feet in the air. It's not pleasant when doing these decomposition bodies when there are large maggot balls spilling over the side of the table and then you're left stepping on maggots.”

Most procedures are much cleaner than you might think, though. Hollywood has led us to believe forensic pathologists are covered in blood but the reality is much less gory.

“Dead bodies do not spray blood as most people commonly believe. Your heart is generating pulse pressure when you're alive. That's not happening when you're dead, so there's no blood pressure, and blood merely kind of oozes passively out, and it's usually not very much at the point of initial incision,” says Patrick.

A forensic pathologist knows death better than anyone. Death comes to us in many forms and in a million different ways that can be recognised during an autopsy by any experienced forensic pathologist, but not all causes of death are as obvious.

“The autopsy is first and foremost an inquiry by structural analysis. We're dissecting the body, looking at actual, tangible, physical structures. So what we cannot see are our physiological processes. We can't see a functional event after that event has stopped. So two prime examples of what we cannot see at autopsy would be seizures and cardiac arrhythmias. We can say it’ll be a reasonable explanation but we can’t say for certain,” says Patrick.

Post-mortem examinations are known for providing answers for grieving families. They put murderers behind bars and victims to rest. Patrick explains that forensic pathology is an area of study that works with dead bodies, but it is actually first and foremost preventative medicine.

“I know everybody thinks, how's that possible? The person is already dead. But we're not doing this for the dead person. We're doing this for the community that we serve. We are trying to identify risks to public health and therefore measures to prevent it.”

The trauma scene cleaners

No matter what day of the year, the frontline staff of A Cleaning Service put on hazmat suits to remove reminders of the tragic way people have died, so their families or next-of-kin don’t have to.

Depending on the level of decomposition, and the amount of time a body has been left unattended, the deceased will leave fingernails and hair behind and leaking bodily fluids will seal their final moments as a stain.

The family-run UK company - sisters Claudia and Alice, stepmom Alison and dad, Nick Linton-Butt - run a specialist team trained in trauma crime scene and deceased cleaning. They'll remove the tell-tale signs of death that’ll only serve to traumatise grieving families and loved ones.

“A lot of what we do is blind," says the 45-year-old company director, Alison Linton-Butt. "We’ll go in there after removing the body and assessing the area. You can get flies or maggots depending on how long the individual has been unattended. The decomposition process starts four hours after the person has died, so you’ll get strong odours that will start after the gasses have been released from the body.”

Working alongside death is not a job all of us are capable of. A strong stomach is a necessity for any trauma cleaner, but most importantly, they must be mentally and emotionally prepared to tackle any situation. And no two calls are the same for A Cleaning Service. From a young mum who died from heroin abuse to an individual not discovered for over five months. Each scene tells somebody’s story and can have a deep physiological impact on those who enter.

“There was one job that I did, where a young student, unfortunately, committed suicide. The family then had to come into their child’s accommodation to collect his belongings. So it's the actual physiological experience of it, having to go into that kind of scenario, which affects someone the most, so yeah, it affects both ends of the stick,” says Alison.

There is more to this job than just cleaning. It’s an emergency service that serves a crucial role at the end of life and has to be dealt with compassion and empathy. But, unlike other emergency services, it’s not free, says 23-year-old sales executive, Alice Linton-Butt. “It can be especially traumatic for people that can't afford it. They feel pressured that maybe they should clean it up themselves and that can be really hard for them, especially if it’s a younger person calling about a parent. It can also put their health at risk from all the pathogens that come with biohazard waste.”

Alison adds: “There was an unfortunate incident last year where a lady phoned because her husband committed suicide in the house. We were three hours away and we left to get there immediately. I was actually in the bath at the time, but from the customer’s point of view, they must get that urgent response so they can process the traumatic experience.”

On the long drive back, the cleaners are often left to reflect on what they have seen. This can be difficult but then they remember why they do it. Business development manager, Claudia Linton-Butt, 26, says: “In a way, it’s a very rewarding job. We have the privilege to help someone by giving back their home and that’s why we do it.”

Display images by Mitja Juraja and Mike Bird on Pexels.